AN ETHICAL TRADITION: WHAT OXFORD’S TEACHERS AND STUDENTS HAVE BEEN SAYING DURING 250 YEARS

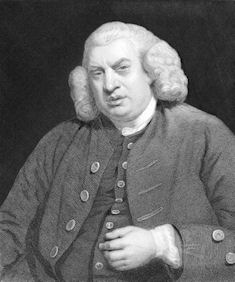

During the eighteenth century, vivisection in Britain was the work of “virtuosi”, pursuing their researches in private laboratories or college rooms. Their novel and hideous cruelties are what Dr Johnson condemns in this first quotation:

Among the inferior professors of

medical knowledge is a race of wretches, whose lives are only varied by

varieties of cruelty; whose favourite amusement is to nail dogs to tables

and open them alive; to try how long life may be continued in various

degrees of mutilation, or with the excision or laceration of the vital

parts; to examine whether burning irons are felt more acutely by the bone or

tendon; and whether the more lasting agonies are produced by poison forced

into the mouth, or injected into the veins […] It is time that universal

resentment should arise against these horrid operations.

Among the inferior professors of

medical knowledge is a race of wretches, whose lives are only varied by

varieties of cruelty; whose favourite amusement is to nail dogs to tables

and open them alive; to try how long life may be continued in various

degrees of mutilation, or with the excision or laceration of the vital

parts; to examine whether burning irons are felt more acutely by the bone or

tendon; and whether the more lasting agonies are produced by poison forced

into the mouth, or injected into the veins […] It is time that universal

resentment should arise against these horrid operations.

Samuel

Johnson, Pembroke (The Idler, 5 August, 1758)

By the middle of the nineteenth century, scientific research was becoming more collaborative and institutionalised. Though a few Oxford colleges already had their own laboratories in which animals were kept and used in experiments, vivisection was officially introduced to the University in 1882, with the appointment of its first Waynflete Professor of Physiology and the building of a dedicated physiology laboratory. The quotations from that time reflect the great dismay and controversy which this development caused.

We have now, I think, seen

good reason to suspect that the principle of selfishness lies at the root of

this accursed practice.

Charles Dodgson (Lewis Carroll),

Fellow of Christ Church ('Some Popular Fallacies about Vivisection',

in The Fortnightly Review, 23 June, 1875)

The passing of this Cruelty to Animals Bill is a great step

in the history of mankind.

George Rolleston, Linacre Professor

of Anatomy and Physiology (Scientific Papers and Addresses, ed.

Turner, 2 vols, 1884, vol.I, p.ix)

[note: Professor Rolleston was

referring here to the 1876 ‘Vivisection Act’. This Act was indignantly

resisted and then much weakened by the professional physiologists, but it

did at least establish the principle that scientists should not make up

their own morality, if any, as they went along. Rolleston was one of the

very few physiologists who pressed the case for this Act, and his voice

did much to give it what force and scope it did have. He probably suffered

professionally as a result.]

[note: Professor Rolleston was

referring here to the 1876 ‘Vivisection Act’. This Act was indignantly

resisted and then much weakened by the professional physiologists, but it

did at least establish the principle that scientists should not make up

their own morality, if any, as they went along. Rolleston was one of the

very few physiologists who pressed the case for this Act, and his voice

did much to give it what force and scope it did have. He probably suffered

professionally as a result.]

Who, not a

vivisector, can read without a shudder these papers in the Nineteenth

Century, and Mr Simon’s address to the Medical Congress in 1881, a

shudder at the utter and absolute indifference displayed to the terrible and

widespread suffering which the practice the writers are defending entails

upon helpless and harmless creatures? Yet who are these writers?

Chosen men; bright examples (we are told) of the scientific class, persons

whose names alone are to be arguments in their favour. If these men write

thus, and it is incredible that merely as men of common sense they should

affect an indifference they do not feel, what will be the temper of mind

of the ordinary coarse, rough man, the common human being, neither better

nor worse than his neighbours, of whom the bulk of the medical

profession, like the bulk of every other profession, is made up?

Lord Chief Justice Coleridge, Balliol (The Fortnightly

Review, XXXVIII, Feb. 1882, pp.225-36)

Nothing

can justify, no claim of science, no conjectural result, no hope for

discovery, such horrors as these.

Henry (later Cardinal)

Manning, Merton (Speech, 21 June, 1882: quoted in The Extended

Circle, ed. Jon Wynne-Tyson, 1990, p.296)

People in general are even now only beginning to see what

Lawrence and Bentham saw long ago, that animals have the same natural

rights of life and liberty as ourselves, and for the same reason – that

these rights are the necessary outcome of a capacity to feel pleasure and

pain – and that violations of these rights (from the killing of a cobra to

the killing of an ox for food) cannot be justified unless they are

conditioned by ‘the struggle for existence’.

E. W. B. Nicholson, Trinity: Bodley's Librarian

(Reasons for non-placeting the following form of decree in Convocation., 1883)

The promoters of the Memorial sincerely trust that they

will not be suspected of any desire to hinder physiological teaching or

research in the University: they are only anxious that physiology, like

other branches of science, should be pursued by means free from

reproach.

E. W. B. Nicholson et al (Memorial to the Hebdomadal

Council of the University of Oxford, 1883)

I

heartily wish success to your endeavour to keep an evil thing out of

Oxford.

I

heartily wish success to your endeavour to keep an evil thing out of

Oxford.

John Mackarness, Bishop of Oxford (letter to E.W.B.

Nicholson, 1883)

[…] my resignation was placed in the Vice-Chancellor’s

hands on the Monday following the vote endowing vivisection in the

University, solely in consequence of that vote.

John Ruskin,

Christ Church, Slade Professor of Fine Art (letter to The Pall Mall

Gazette, 24 April, 1885)

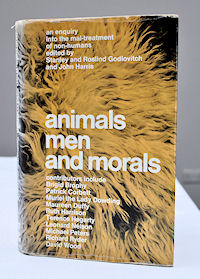

Disgust at vivisection, so vocal at Oxford in the 1880s, did not then disappear (see the first quotation below, from C. S. Lewis), but the controversy went quiet for many years, until the whole subject of animal rights was dramatically renewed in 1971. In that year, a group of Oxford post-graduates produced the book Animals, Men, and Morals, from which several quotations are taken here. Following those is a quotation from Peter Singer’s classic Animal Liberation, a book which grew out of a review he wrote of Animals, Men, and Morals. His book has been in print ever since, nor has the subject lost any of its urgency meanwhile. The last few quotations show it active in literature, politics, and the press.

The victory of vivisection marks a great advance in the

triumph of ruthless, non-moral utilitarianism over the old world of ethical

law: a triumph in which we, as well as the animals, are already the victims,

and of which Dachau and Hiroshima mark the more recent achievements.

C. S. Lewis, Magdalen College (Vivisection, 1947, p.11)

Once we acknowledge life and sentience in other animals, we are

bound to acknowledge what follows, their right to life, liberty and the

pursuit of happiness.

Once we acknowledge life and sentience in other animals, we are

bound to acknowledge what follows, their right to life, liberty and the

pursuit of happiness.

Brigid Brophy, St Hilda's College

(Animals, Men, and Morals: an Enquiry into the Maltreatment of

Non-humans, ed. Godlovitch and Harris, 1971, p.128)

Our conviction, for reasons we have given, is that we

require now to extend the great principles of liberty, equality and

fraternity to the lives of animals. Let animal slavery join human slavery in

the graveyard of the past!

Professor Patrick Corbett, Balliol

College (Animals, Men and Morals: an Enquiry into the Maltreatment of

Non-humans, ed. Godlovitch and Harris, 1971, p.238)

There is nothing to indicate that an animal values its

life any less than a human being values his.

Rosalind Godlovitch,

St Hilda's College (Animals, Men and Morals: an Enquiry into the

Maltreatment of Non-humans, ed. Godlovitch and Harris, 1971, p.164)

When all the arguments are over, if one has not been

convinced by the weight of reason, one’s nightmares and day-dreams should

still be filled, if one’s actual experience is not, with the vision of

countless other animals dying and dead in the misconceived interests of

man.

David Wood, New College (Animals, Men and Morals: an

Enquiry into the Maltreatment of Non-humans, ed. Godlovitch and Harris,

1971, p.211)

We are in the midst of an emergency in which appalling suffering is being

inflicted on millions of animals for purposes that on any impartial view

are obviously inadequate to justify the suffering.

We are in the midst of an emergency in which appalling suffering is being

inflicted on millions of animals for purposes that on any impartial view

are obviously inadequate to justify the suffering.

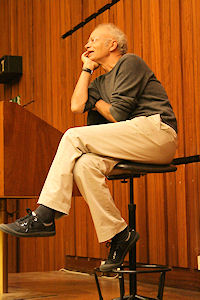

Professor

Peter Singer, University College (Animal Liberation, 1995 (1975),

p.85)

It is in the name of science, and with the specious

bribe of release from all our ills, that we have been cajoled and threatened

and insulted into permitting the continued torture of our kindred and the

continued blunting of the sensibilities of those who come to work in

laboratories. Let no-one rely on common decency in such a situation: the

pressure of one’s professional peer-group, the atmosphere of dismissive

tolerance of all outside the clan, the calm assumption that this is what we

do, are all far too strong for most of us to resist.

Professor

Stephen Clark, Balliol and All Souls Colleges (The Moral Status of

Animals, 1984 (1977), p.141)

“What specific benefits were expected to result from

these tests -experiments - whatever you call them?”

“I think the best

way I can answer that,” replied Dr Boycott, “is to refer you to paragraph

er - 270, I think - yes, here it is - of the 1965 Report of the Littlewood

Committee, the Home Office Committee on Experiments on Animals. ‘From our

study of the evidence about unnecessary experiments and the complexity of

biological science, we conclude that it is impossible to tell what practical

applications any new discovery in biological knowledge may have later for

the benefit of man or animal. Accordingly, we recommend that there should be

no general barrier to the use of animal experimentation in seeking new

biological knowledge, even if it cannot be shown to be of immediate or

foreseeable value.’“

“In other words there wasn’t any specific purpose.

You do these things to animals to see what’s going to happen?”

Richard Adams, Worcester College (The Plague Dogs, 1983

(1977), pp.386-7)

The animal rights brigade ask deep questions which I for

one have not seen answered yet by the defenders of vivisection and torture

of animals in laboratories.

A. N. Wilson, New College

(Evening Standard, 30 July, 2004)

Very often, people are inclined to be dismissive about

the importance of animal welfare and say that we should attend to other

priorities. They think that concern for animals is based on misplaced

anthropomorphism or sheer sentimentality, whereas I believe that how we

treat our animals is a measure of society.

Ann Widdecombe,

LMH (House of Commons, January 10, 2006)

[…] the university could do so much more to develop,

implement and promote non-animal alternatives. There is growing sensitivity

on this issue. It would be good to have a rational debate, concentrating on

alternatives; and even better for the university to end up on what many

regard as the ethical side.

Sir David Madden, Merton (letter

to The Times, July 20, 2008)

Oxford’s ethical tradition needs no further illustration. It will remain a vital tradition for thinking people at Oxford and beyond for as long as the immorality of animal exploitation itself continues.